I promise you won’t have to use either Google or a dictionary while reading this. In this post I will teach you the core concepts about everything from “deep learning” to “computer vision”. Using dead simple English.

You probably already know what self driving cars are and that they are considered the dope shit these days, so if you don’t mind I’m going to skip any high school essay-ish introduction. :)

But I’m not skipping my own introduction: Hi I’m Aman, I’m an engineer, and I have a low tolerance for unnecessarily “sophisticated” talk. I write essays on Medium to make hard things simple. Simplicity is underrated.

How do self-driving cars work?

Also called autonomous cars, they work on the combination of 3 cool fields of technology. Here’s a brief introduction to each of them, and then we will go into depth. By the end of this essay, you will know enough about all these technologies to be able to hold an intelligent conversation with an engineer or investor in these fields. Things like “artificial neural networks” won’t sound like magic spells or sci-fi film words anymore.

By the way, I’ve categorized some things into roughly separate high-level “systems”, but of course in practice these systems are all highly interconnected without clearly defined boundaries and have a ton of stuff going on under the hood.

Check out the Lidar sensor on top. It’s a spinning laser beam.

Computer Vision (ooooooohhhhh sounds so cool): The technology which allows the car to “see” its surroundings. These are the eyes and ears of the car. This whole system is called Perception. Basically we use:

1. Good old cameras, which are the most important (simple 2 megapixel cameras can work fine),

2. radars, which are second-most important. They throw radio waves around, and like ultrasound you detect the waves that bounce off objects and come back,

3. and lasers, which are cool to have but they are pretty expensive nowadays, and they don’t work when its raining or foggy. Also called “lidar”. You can say they’re like radar but give a little better picture quality, and lasers can go pretty far so you have greater range of view. The lasers are usually placed in a spinning wheel on top of the car so they spin around very fast, looking at the environment around them. Here you can see a Lidar placed on top of the Google car:

Deep Learning: It is a technology that allows the car to make driving decisions on its own, based on information it gathered through the computer vision stuff described above. This is what trains the ‘brain’ of the car. We will go into detail about this in a minute.

By combining the two even on a basic level, you can do some interesting things. Here’s a project I made, detecting lane lines and other cars on the road using only a camera feed.

Robotics: You can see everything, and you can think and make decisions. But if your brain’s decisions (eg: lift the left leg) can’t reach the muscles of the leg, your leg won’t move and you won’t be able to walk. Similarly, if your car has a ‘brain’ (=a computer with deep learning software), the computer needs to connect with your car’s parts to be able to control the car. Put simply, these connections and related functions make up ‘robotics’. It allows you to take the software brain’s decisions and use machinery to actually turn the steering, press and release the throttle, brakes etc.

Navigation and Path Planning: Even after being given all the above, ultimately you still need to figure out “where” you are on the planet and the directions for where you want to go. There are several aspects to this, like GPS (your good old navigation device, which takes location information from satellites), and stored maps, etc. You also mix in computer vision data. There are also several ways to do path planning (maneuvering over short distances).

So the car controls its steering and brakes etc based on the decisions made by its brain, and these decisions are based on the information received through cameras and radars and lasers and the directions it receives from the navigation programs. This completes the whole system of a self-driving car.

Tidbit (feel free to skip)

Self driving cars come in many “levels”, from Level 1 to Level 5, based on how independent the car is and how little human assistance it needs while driving. Oh and there’s also Level 0, which is your good old manually operated car.

Level 5 means the car will be 100% self-driving. It will not have a steering or brakes, because it’s not meant to be driven by people. These cars don’t exist yet, and cutting-edge cars are still at Level 3 and at most Level 4.

Deep Learning Explained for Chimpanzees like Myself

Let’s say you were a wildlife safari enthusiast, and I was your super-idiot friend. I’m going for safari in Africa next week. And you give me some advice: “Aman, stay away from the fucking elephants.”

And I ask you back, “What’s an elephant?”

You will most likely say, “You stupid jerk, elephants are… okay never mind, here’s a photograph of an elephant, this is what it looks like. Stay away from them.”

And then I go off to safari.

Next week you get to know that I still managed to run into an elephant and almost ended up getting trampled. You ask me what happened.

I reply, “I don’t know, I did see this huge animal but it didn’t look anything like the photo you showed me, so I thought it was safe to play with and I went ahead and pulled the little wagging thing. Here’s the photograph of the animal I took before that…”

You: ……….

You: “Okay, Aman. I’m sorry, my bad. I expected too much from your brain. Let me give you a “cheat code” which you need to follow when you’re on the safari next time. If you see anything that looks brown-ish from all angles, seems to have four leathery legs like pillars, large flapping ears, and a thick long nose coming out of its face like a big tube, and is fat and bigger than you are, then that’s an elephant and you need to stay away.”

Next month I go back to safari again (hey, it’s my hypothetical story and I can go to safari as many times as I want) and I don’t run into any elephants this time, because your “cheat code” works well.

How did you come up with that “cheat code”? It’s because you’ve already seen an elephant from all different sides, and you picked some features of an elephant which remain pretty same regardless of which angle you view the elephant from. So you had lots of FEATURES of elephants to think about that you derived from all the DATA about elephants that you collected over your lifetime, and that helped you to form a mental picture of the most obvious features of an elephant, and gave them to me as a cheat code. Realize that I don’t have to really “know” exactly what an elephant is, I just have a cheat code that helps me recognize an elephant. But that cheat code works almost as well as knowing what elephants are! (And from a philosophical standpoint — do you really know what an elephant is? Or don’t we all just perceive the world through similar cheat codes and judgements? Something to think about.)

But why wasn’t it okay to just show me one photograph (the one you showed earlier) and assume it was enough for me to get the idea? Because I (being an idiot of course) took that photograph as the “holy truth” — I assumed that every elephant will look *exactly* the same as that photograph, and will be a near perfect match.

Deep Learning works in a VERY similar way.

Here’s the basis of deep learning: artificial neural networks, which I’ll explain now. They are also called deep neural networks.

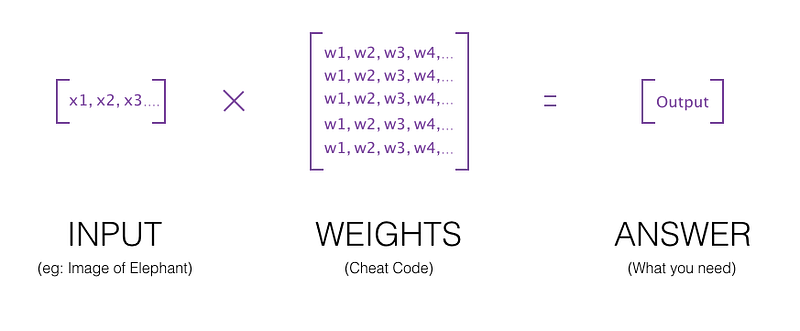

First, I assume you know a little bit of math from high school. You know what a matrix is, right? And that you can multiply a matrix with some other matrix? That’s literally the only piece of math that I need you to know for this essay. But don’t feel bad if you don’t know this! I grew up hating math myself. Here’s a refresher anyway:

Remember what a matrix is.

An artificial neural network (ANN) is some really fancy stuff but I’ll take you on the journey with baby steps. You see, the human brain is made up of a network of many cells called “neurons”, which is the inspiration for ANNs. This is what it looks like on paper:

An ANN is a magic box, which takes in an input and gives out an output. For example, suppose you wanted a magic ANN which takes in a photograph and can tell if the photograph is of an elephant or not. You put a photo into the box, and out comes an answer “yes” or “no”.

Or, you put in a photograph of the road ahead and you want the ANN to tell you if you should slow down or speed up. And the answer comes out, “speed up!”

How does it happen? How can you create this ANN?

Put simply, an ANN is like a simple version of a human brain. First you train it with data. When you give data to an ANN, it creates a “cheat code” which helps it make decisions next time. (I’ll give a detailed example in a second) This “cheat code” is called “weights” of the ANN. You saw that ‘matrix’ earlier? You can say that the first matrix [x y] matrix is an input, and the second matrix [u w] matrix is the set of weights or cheat codes. When you multiply the input with the weights, you get an answer.

The ANN can be of many different varieties, and based on how you design it, can either give a “yes or no” answer, or, for example, it could give a specific number, or a list of different numbers, etc. You can choose what kind of output it will give and what kind of input it will receive, and how large and complex it will be, which makes it extremely versatile. You can build neural networks that take videos as inputs, voice samples, images, or text paragraphs, etc. Of course, all these are converted into numbers on a computer automatically, and there will be a huge matrix of “weights” which will be multiplied to that input, generating an output which is your answer.

But I’m sure you still don’t understand completely. How do you “train” the ANN to give you meaningful outputs?

Let’s say you want to train an ANN to recognize elephants.

So you create a fresh ANN which takes a certain type of input and gives out a certain type of output. At first, this ANN doesn’t really know anything about the problem it’s trying to solve. It’s just like me from the original elephant example — before you showed me the first photograph of an elephant, I had no idea what an elephant even was. If you asked me right there and then to look for an elephant in a photograph, I’d probably have picked something randomly. So you can say that initially, I had some random bullshit cheat code right? But the moment you show me ONE elephant and tell me that it is an elephant, suddenly I adjust my random cheat code and now I have some idea of what elephants are. My cheat code is not random anymore, and if I saw an elephant from the front I’d probably pick the right answer! So I have updated my cheat code when I was given more information. And the more different photographs of elephants I have, the better my cheat code becomes at giving the right answer. I still don’t know “what” an elephant is, but I’ve seen enough correlation in different photographs to recognize the most special features of an elephant and stay away from them.

Similarly, when you first create an ANN, you start by giving it a random set of weights (=cheat code) to start with. Then you show it an input image (photograph of an elephant), and also tell it the output you expect (answer “yes”). The beauty of ANNs is that if you give it an example input and its corresponding output, then it will adjust its cheat code so that it can repeat that correct answer next time. It will change the numbers in that matrix of weights the more data you give to it, to be able to match your answers. This is why, you can start with a random set of weights and with time the ANN will adjust them so that they work well as a cheat code! Cool right? That’s how the ANN “learns”. The more data you give it, the more it adjusts its weights, and the more accurate it becomes.

As I explained earlier already, how this happens is through matrix multiplication. The matrix of weights for this ANN will have values such that if you multiply it with your input image (the image will be converted into numbers), you can get an answer. Usually, there’s not just one matrix of weights, but a series of matrices which you multiply one after the other. But the concept is the same as you see in the image below:

But that’s not enough. Remember that the ANN is not smart — it works on cheat codes, after all. If you only gave it elephant photographs to look at, and keep saying “yes” for every photo, what do you think it will do?

It will be lazy and assume that every photograph is an elephant! It will adjust its weights (cheat code) in such a way that regardless of the photo it is given, it will always output a “yes”. This is called “underfitting”, which basically means you made the mistake of thinking that your idiot friend is smart. Your ANN has become biased towards a particular answer. To prevent this, you need to also feed it counter-examples which have the answer “no”. So you also mix in lots of example photos which are not of elephants, but even lions, cows, human beings, squirrels, pikachus and bulbasaurs, sea horses and… (sorry, I got carried away) and now the ANN will be forced to adjust its cheat code more carefully. Now you’re increasing its accuracy and making it more reliable! Or, you can also have “overfitting”, when the ANN’s cheat code is still lazy but it’s now so super smart that it begins to memorize the entire training data you give it! This often happens when your ANN is very large and deep, so in a way it just begins to store all the information you give it. It becomes super good at answering on your training data but it fails when given a new example that it hasn’t encountered before. It’s no longer working like a cheat code, but rather it has become like a dictionary of images. You can prevent this by reducing the size of your model (by randomly dropping some of the weights), or by increasing the variety of data. The former is called “dropout” (pretty straightforward but a very crazy idea), and the latter is called “balancing the dataset”.

You have also learned your lesson from the safari example earlier, and now you will be careful to show it other photographs of elephants from many different angles so that it doesn’t make the same mistake that your idiot friend made. This is why researchers/engineers often “augment” their training data sets to include mirror reflections or brighter/darker versions of the same images etc, to increase the variety of their data. This helps make sure that the ANN can become as accurate as it can. You want the cheat code to be so super “robust” that it works as well as real humans, or better.

By the end of the training, with enough balanced data and augmentation etc, you will have a trained ANN (also called trained model) which can recognize elephants in images with reasonable accuracy, and also know when not to recognize an elephant.

“Overfitting”, the word you encountered just two paragraphs ago (=network becoming too smart and acting like it has just memorized your data), is a very common term in the Deep Learning lingo and you now know what it means. (Underfitting is a less troubling problem because it’s fairly obvious to diagnose and easy to tackle.) Someone might say, “oh man my model isn’t working so well on new data, I guess it is overfitting” and you’ll say, “did you try to augment the training data?” and you will instantly own the night. The other person might even assume you’re a deep learning engineer yourself! (If they do, tell them “Oh no, I just follow Aman on Medium”. When they ask who I am, please pretend and say “oh you don’t know? He’s the coolest guy in this space!”).

The process of adjusting weights (updating the cheat code based on data) involves something called backpropagation. While training, whenever you show the ANN an example input (let’s say a kitten) and then tell it the answer (“no it’s not an elephant!”), it will first try to use its current cheat code to come up with its own answer. If the answer is RIGHT, then it doesn’t need to adjust its cheat code, right? The lazy ANN will update its cheat code only when it makes a mistake. So only if the ANN’s answer was WRONG, it will have to adjust its weights (=cheat code) by a tiny bit and test the weights again. This adjustment algorithm is called BACKPROPAGATION. The “mistake” made by the ANN sends ripples through the matrix of weights, changing many of their values. So you can say that the error propagates back through the network. Again, this is why you can always create the ANN with random weights initially, and over time it will adjust them on its own.

Put simply, if you take a cheat code to an exam, and get some of your answers wrong, then you will likely upgrade your cheat codes for the next exam in that subject to have higher accuracy. The process of editing/rewriting your cheat code after every exam, based on its grade, is called backpropagation.

Now look at the graph image of a “neural network” again. You see that thing called the “hidden layer”? Well, the ANN is made of layers of neurons, these neurons carry the weights as values. They are called “hidden layers” because you don’t need to know the exact weights in the network! You can print the values out, for sure — but it’s useless to look at a matrix which can run into millions or billions of small numbers. It’s a cheat code, and it updates itself based on the inputs you give it, and that’s all you need to know.

This is why deep learning is often considered a “black box” system. If you’ve ever programmed before in any language, you are used to writing down explicit instructions for the program for everything. But here, you can’t see the underlying ‘cheat code’ the computer created for itself to use in place of a written algorithm.

Coming back to self-driving cars, let’s say you took photographs from different cameras around the car at a particular millisecond, and took all the data collected from the radar and lidar (=lasers) too, and combined them together in a list, and used that list as the input for your car’s ANN. And the output you expect from the network is a long list of the steering angle, the throttle/braking value, whether to light up the headlights or not, whether to honk or not, etc. These are your “labels” to be predicted by the ANN.

The kind of deep learning in which you explicitly train the ANN using specific data gathered by humans, is called “supervised learning”. For each data sample, you have the data and you have the label.

So here’s an example of how you will “train” the car’s brain. First you will simply drive the car normally by yourself, but keep collecting the input data from sensors and cameras etc. There is also equipment which measures, for each millisecond of data, the steering angle and throttle pressure etc that you made while driving. Then once you get back home, you can start ‘training’ the ANN on all that data you collected while driving. The ANN will update its cheat code to take your computer vision input and try to mimic your driving decisions as closely as possible.

This is known as behavioural cloning, and it is in principle similar to what most car companies are doing nowadays — collecting driving data, and making their cars ‘practice’. After every training trip, the car will become better and better at making decisions. Behavioural cloning is only used for small parts of the system’s workflow and the driving process. There’s also a lot of manual tuning and human-written instructions and checks to make sure the car doesn’t run around like a headless chicken led by a poorly trained artificial neural network.

Everything else being similar, driving data is the biggest winning factor in the race to develop self-driving cars.

Now — you know what “Deep Learning” is, and what it does. You know what deep neural networks are (= ANNs), and how they work (weights = cheat codes, backpropagation = adjusting the weights based on a given example test). You also know that you should have a large and balanced dataset so that the network doesn’t overfit (get lazy or too smart in setting its cheat codes).

Congratulations! I kid you not, this is more of an achievement than you think!

Computer Vision

Remember this scene from The Terminator?

Schwarzenegger enters a bar naked, and looks for someone to take clothes from. This must be what comes to your mind when you think “computer vision”, and you are partially right.

Self driving cars can also see the world like that. The major purpose of computer vision techniques is to process the camera images to detect lane lines, track other vehicles and pedestrians, look for any bumps or holes in the road, measure the distance between the car and other objects etc.

There’s no one technique or underlying technology for computer vision — rather, often it comes down to simple image processing. You are limited only by your imagination and ability to design complex algorithms, and if you’re good at geometry that is another plus. For example, a popular way of processing the camera images involves looking at how quickly the colors change in horizontal and vertical directions. That is called a “gradient” and it can be used to find edges. Here’s an example:

These are all created by using simple techniques using a popular library of computer vision functions, called OpenCV. You should know about OpenCV, because it is the most popular library for this purpose. Every robotics or deep learning guy knows about it.

Taking the above example further, the images you see are simply a representation of ones and zeros on a rectangle. The ones are white, and the zeros are black! You can select the pixels in any one region of the picture and play around with it. This is how I detected lane lines and came up with my project output as seen at the beginning of this blog post.

Another common technique used in computer vision to detect objects is called stereo vision. Don’t be thrown off by the seemingly complex name, stereo vision simply means looking at something with more than one eye (you do it all the time). When you see something with two eyes, you have a better estimate of how far it is and what shape it has. Similarly, cars use more than one camera on either side and combine the images to see the world more realistically.

What about adverse conditions like snow, rain, etc when it’s difficult to see the road? Well, let’s not forget about the other two sensors (radar and lasers). Even when any two sensors don’t work so well, the system is designed such that third one should still be quite reliable (but it’s an ongoing field of research and we’re not perfect yet). Moreover, if the car’s neural networks have already been trained to drive in such conditions, the car should have some idea of how to make decisions. Again, as I said earlier, the foremost priority is about collecting enough data. The more you train, the better the car gets. Period.

I won’t go into more detail about computer vision, as it is a very broad field. Just know that it’s not sci-fi, and there’s nothing “magical” about it. It’s just about using your imagination to play with images. There are other techniques, which you can read about in this very short and simple page:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/darpa/see-nf.html

Robotics and Navigation

Actually, I’m not going to spend too much time here. In principle, robotics is pretty straightforward (you don’t need fancy imagination to understand what happens)— you basically need to know about something called an actuator. However, even though it’s straightforward to imagine, it’s hard to actually execute well!

An actuator is a device which takes an electrical signal as input, and converts it into a physical action. It’s not too complicated, often it just has a motor inside it that rotates by a certain angle based on the strength of the electrical signal it receives. Actuators come in all shapes and sizes, there will be one in the steering wheel, one for the throttle, brakes, gears, the engine etc. You get the idea.

For Navigation, apart from the GPS/maps/computer vision technologies, you should also know about a really cool technique called “dead reckoning”. It involves calculating your current position based on your speed and distance travelled and knowing the history of all the turns you made up until the present moment, etc. You remember the sucky Sherlock Holmes movie with Robert Downey Jr? There’s a scene in which he gets kidnapped and taken inside a horse carriage and blindfolded, but after they arrive at the destination he magically knows exactly where he is. Do watch the first few minutes of this scene and you’ll understand what “dead reckoning” is. The system works pretty much like Sherlock Holmes.

The principles of dead reckoning are used for “localization” (estimating where your vehicle is), and then that information is used for path planning (where you should go).

Alright! Now you know should have a very good idea about how self-driving cars work. Here is what we have learned:

- Deep Learning — cheat codes, balancing the training data, overfitting and other issues, why deep learning is a “black box” etc.

- Computer vision — camera, radar and lidar sensors, stereo vision, how you can process images creatively to extract many different kinds of information, there’s a popular programming library called OpenCV.

- Robotics — what actuators are.

- Navigation — you learned that apart from the GPS and stored maps etc, cars use a Sherlock Holmes -style technology called “dead reckoning”.

So… do you feel more dangerous and awesome now than 20 minutes ago? :)

My purpose was not just to give you confidence, but also appreciation. It takes a lot of really smart people to do the million different things required to successfully build a self driving vehicle, and now you can have more respect for them.

Now, some thoughts on the “AI will take our jobs and then kill us” discussion

I want you to notice an interesting thing about what you learned just now. You learned that every neural network is designed and trained to take a specific kind of input, and then give a specific kind of output.

Even if you take one huge neural network and used it to act as the brain of a self driving car, you’ll still need to connect it to inputs from all the sensors and cameras around the car, and the GPS and maps, and also connect the outputs of the neural networks to all the hardware and actuators that make the car move. As you learned already, a neural network is a sequence of matrices multiplied or added to each other. If you don’t connect it to an input or an output, it’s a dead mathematical expression just like any other.

But let’s say you irresponsibly take a poorly trained neural network and use it to run a dangerous machine like an eye surgery robot. It’s operating on an eye which has some very rare condition that neither the doctors nor the neural network has been trained to detect. The robot makes an error that permanently damages the eye. Now in this hypothetical scenario, I’m sure that next day newspapers around the world will talk about how AI woke up and decided to kill a person. But now that you have read the entire essay above, I hope you can see why this is bullshit.

You could make an argument, that hey – the whole universe, even human brains, are essentially made up of mathematical expressions at the deepest level, and thus some matrices are more evil than others. So maybe a neural network can potentially be evil. Maybe while training the neural network, you rearranged its weights in such a way that it becomes evil.

Even IF this could be true, it’s still not a good argument. Even if that poorly made (or “evil”, as newspapers would call it) AI software was simply never installed on a real robot, it could never have made any mistakes.

I personally feel that the use of AI in the real world should be regulated, to ensure that it doesn’t harm people. It should be similar to the medical industry — people should be free to develop a new drug in their lab in test tubes. BUT if you want to test your new drug on animals or human beings, you have to ask the government for permission and prove that it is ready to be tested.

It’s all about how you decide to USE a software. Engineers should be responsible for building software properly, and also for deciding whether their software is ready to be used in the real world or not.

And that’s it! If you found this helpful, let me know in the comments. I will feel good about it.