The Challenge

I’m extremely optimistic about humanity’s potential. Human ingenuity is amazing.

But humanity’s progress in science and tech is slower than it should be, and our efforts are laughably inefficient. Our challenge as a species is how to effectively utilize and deploy the sum total of our intellect and resources towards shared goals.

In many ways, we’re still a nascent civilization, and the vast majority of us are still subsisting like other animal species — on average, our daily activity is still oriented around survival (earning a living), reproducing and nurturing our progeny, and trifling pleasures.

Only a tiny few among us are contributing to the technological advancement and evolution of our species, which is, on a macro level, crucial to our long-term survival. And even those who do, face an incredible amount of friction and tough barriers that further slow down scientific progress.

The reason is that humans are extremely limited in their ability to utilize the ideas and experiences of other humans to accelerate their own discovery and problem-solving processes. Here’s why:

- Knowledge barriers: Our ability to learn is limited. It’s hard to know enough about other disciplines to fluidly extract insights and reapply them. It’s also hard to start, when there is an overabundance of information.

- Language barriers: Billions of people only speak their local language.

- Resource & information sharing: Free movement of information and resources (funds, materials, equipment, etc) road blocked by geographical, economic, political, or cultural/social barriers.

These limitations are not due to physics but due to the biological limitations of the human brain.

However, we’ve arrived at a place where all of these problems can be solved, to a large extent, using technology. By building the right tools and infrastructure, we can make untold leaps in our species’ technological journey.

DenseLayers (and its parent company, SANPRAM Research Inc) was founded to work on exactly this mission.

DenseLayers exists to accelerate frontier science.

And we are already making progress, by building several patent-pending tools to address all the limitations mentioned above. As technology advances, our products and infrastructure will keep getting better, and humanity will be able to extract and deploy more and more of its unutilized intellectual power.

Reforming “Science”?

The crux of the issue is to reform the way humans participate in “scientific discourse.”

The format of discourse has evolved greatly throughout history, but a few things have stayed the same: it has always been in small pockets, with limited geographical scale, and the spread of scientific knowledge has been painfully slow.

Science or math would usually travel via trading routes, such as how the Arabs took the zero (0) from Southern India and brought it to Europe. Chinese alchemists invented gunpowder as a medicinal substance decades before they shot their first “fire arrow,” and a good century or two before it started traveling westward in large quantities on the backs of Mongol horsemen.

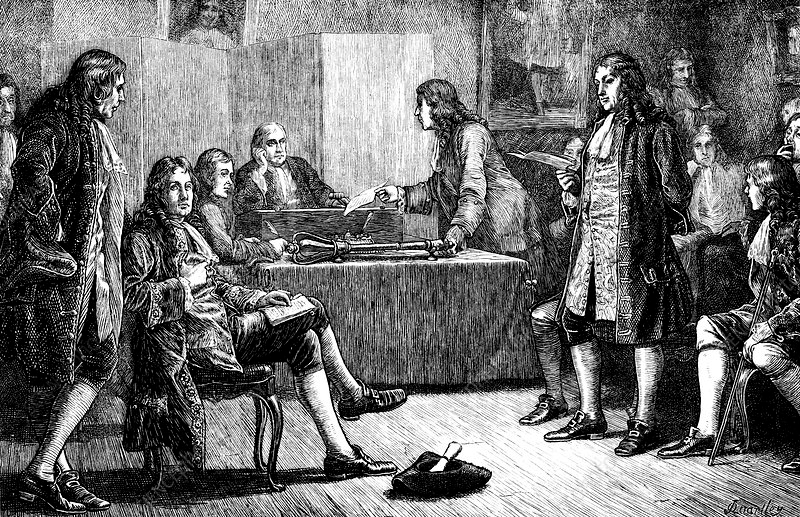

Overall, from ancient universities to “learned societies” (where affluent intellectuals would gather during the weekend to have fun talking science), sharing scientific findings with others has been an extremely informal and organic process.

Once the printing press had arrived, the first science “journals” were born in these very societies (such as The Royal Society of London), in the form of newsletters distributed to their members. Even Benjamin Franklin’s famous experiment, the “Electrical Kite” was first published as a letter to the Royal Society to be discussed by other members!

This was Science 1.0.

This changed in the mid-20th century, with the advent of large, commercial scientific publications and the structured “academic paper.” All thanks to a shrewd businessman named Robert Maxwell — he first decided to go and acquire every physical science publisher across the seven seas.

After capturing the whole market, he told universities that if they wanted to get published at all, they’d have to give him free labour — and then pay exorbitant sums of money each year to access the very publications they helped fill with their content. The process of distributing scientific findings and ideas also became quite formal and bureaucratic.

This is Science 2.0.

We know the rest of the story. Today, the very research papers that were meant to distribute science far and wide have become harder to read than ever before, even for the top scientists of their fields. They have also become prohibitively expensive to access, making inter-domain knowledge transfer even harder.

At DenseLayers, we are developing a new model for scientific discourse — a “learned society of global scale” — from the ground up.

It will be the first true global interconnected superhighway for science.

Our vision for the platform is that it will look like a collection of frontier research niches — from Deep Reinforcement Learning to Synthetic Biology — ever evolving and cross-pollinating.

It will be the hub, the go-to place where scholars from across the world, regardless of their language or knowledge background, come to publish, consume, and discuss cutting-edge science, with the same fun, informal environment that it was like for millennia.

This is Science 3.0.

Science 3.0 is about restoring the organic and free-flowing nature of the last 5,000 years of science, while also making it 10x more open and universally accessible.

It will be a tough journey, because this has never been accomplished before, but once it’s done, it will have a civilization-level impact on our future.

A 1,000 Year Vision: Reality or Insanity?

DenseLayers is being built to exist, in some shape or form, for the next millennium or longer. It is attainable. Here’s how.

What kind of human constructs typically last hundreds or thousands of years, intact and thriving?

One might think of the Pyramids. The Great Wall of China.

But much better examples are social constructs — such as religions (Christianity?), societies and guilds (Freemasons), centers of learning (Cambridge, U.Bologna), and languages (Sanskrit, Armenian).

In a sense, they’re different forms of communities. Any community that continues to add new members over time, effectively replacing the ones who leave or die, can live forever.

Then, there are ideas and information (teachings of Pythagoras, Socrates or Laozi), etc. They too can get transmitted via person to person and far outlive their source.

By organically building a human community at scale, we see no reason why it can’t uphold itself for millennia, continuously evolving with technology. Even as we evolve past the current computer age, eventually transcending planetary boundaries and connecting astronaut-scientists exploring the galaxy.

This is Just the Beginning

I strongly believe that a universal “scientific network” for the human race is as fundamentally necessary as the internet overall, if not more.

It is the foundation. But it’s not the end-all be-all.

The process of “accelerating science” is in identifying every single source of friction in the scientific research process from A to Z, and building tools to address those problems. From idea / discovery to application, to commercialization, all the way to classrooms — our job isn’t truly done until the whole process is lightning fast and smooth as butter.

Our tools will evolve over time. It’s really a never-ending journey, and we will undoubtedly have to pass the baton to future generations.

At DenseLayers, we’re building the tools that the next Isaac Newtons, Aryabhattas, Marie Curies, and Ada Lovelaces will use to expand humanity’s role in the universe.

And we are hiring.

This article is from my codex.